Jason Cherkis / The Huffington Post

DEC. 30, 6:30 PM EDT

Toby Fischer lets his 20-year-old truck warm up in the dark. Frost has stuck to the windows — “like concrete,” he says. The ice melts slowly, revealing cracks that span the length of the windshield. He shifts into reverse, and the truck skids over a slick patch before the tires grip the road again. Fischer lights a cigarette and rolls down the window.

It’s just after 5 a.m. on a Monday in November. Fischer, a 31-year-old construction worker, has to get from his home on the outskirts of Rapid City, South Dakota, to Fort Collins, Colorado — some 350 miles away — and he has to get there by noon. He’s wearing a Kangol hat, jeans, a T-shirt and, for warmth, a hoodie and a jacket. Outside, it’s in the teens and only going to get colder.

The first stop is his mother’s modular home in Hermosa, just south of the city, where he will change cars. In the distance, the lights of Rapid City are mostly dark or blinking like strings of busted Christmas tree lights. The road is covered in snow, and Fischer can’t see a thing. He fingers his patchy beard and talks at double speed. “I don’t even know where the left lane is,” he says. “I’m just going to assume it’s somewhere right in this area and just go for it.”

The streets in town are empty, and the only noise is the truck’s wheels parting the slush. Some of the traffic signals have been turned off, and Fischer is impatient with the few that are operating. Anxiety is his natural resting state. “Is this light ever going to turn green, or are we stuck here forever?” he says at one intersection.

While he waits, the Kmart across the street sparks a memory. Fischer used to shoot up heroin in the parking lot. “This is all my old stomping grounds,” he says half in awe, half in anger at his former self. “I used to drive up and down this road a thousand times a night.”

Fischer has already checked the weather conditions for the route across the plains of South Dakota, Wyoming and Colorado. Overcast, so not too bad. Snow and high winds are always a possibility. He is more worried, though, about keeping his new job building houses. The pay is decent, and there’s the promise of moving up, maybe becoming a foreman someday. He thinks he’s shown the boss that he can be relied on. But when Fischer called to remind his boss that he wouldn’t be coming in today, he sensed unease on the other end of the line.

“I knew he wasn’t very happy about it,” Fischer says. “The last question he asked me was just about how often I had to go. I was honest about it. I just don’t see the point of lying.”

Fischer is going to an opioid addiction treatment clinic. In Fort Collins, a doctor will meet with him for a half hour and write him a prescription for a month’s supply of buprenorphine, a medication that blunts his cravings for heroin and other short-acting opioids. Fischer has spent a dozen or so years dealing with his addiction. He’d tried 12-step and abstinence-only programs three times, but each attempt at recovery had ended in relapse.

The public health establishment, including the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the World Health Organization, has said that medications like buprenorphine (and methadone), when coupled with counseling, give people with opioid addiction the best odds for recovery. Buprenorphine is also more difficult to misuse than heroin. The synthetic opioid is what’s known as a partial agonist — meaning there’s a limit to how much the medication can affect people who use it.

In the U.S., buprenorphine is mainly sold under the brand name Suboxone, in which form it’s combined with naloxone, the drug that can reverse the effects of an overdose. If someone tries to misuse Suboxone by injecting it, the predominant effect will be that of the naloxone, not the buprenorphine. It’s an important safety feature; think of it like an airbag for those with fierce cravings. Such medication-assisted treatment (known as MAT) has proven to lower overdose rates.

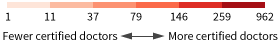

But the U.S. drug treatment system — which is mostly a hodgepodge of abstinence-only and 12-step-based facilities that resemble either minimum-security prisons or tropical spas — has for the most part ignored the medical science and been slow to embrace medication-assisted treatment, as The Huffington Post reported in January. As a result, doctors are generally not involved in addiction treatment. In rural communities, doctors who are certified by the federal government to prescribe medications like buprenorphine are especially scarce: In Rapid City, a town of roughly 70,000 that still manages to be the second-largest city in South Dakota, there isn’t a single doctor who can prescribe buprenorphine for Fischer. There are fewer than 30 doctors in the entire state certified to prescribe it. Fort Collins was the closest place where Fischer and his family could find a certified doctor who was accepting new patients.

Fischer credits the trips to Colorado with saving his life. With the help of his medication, he has been in recovery for 13 months. He stopped hiding from family members and settled down with his girlfriend. The recent birth of his son, Fischer says, has given him a new sense of purpose.

He takes the narrow roads out of Rapid City, heading south. He is surprised his mother hasn’t called him yet to make sure he woke up on time. He’s wondering whether not hearing from her is a sign of faith. “I think that my mom is starting to trust me a little bit more,” he says. Within minutes, his mother calls, wondering where he is.

When Fischer arrives, his mother, Alexandria Anderson, is waiting in the garage with a travel mug full of coffee for him. She has an appointment with the same doctor in Colorado. She’d developed an addiction to the prescription opioid painkillers she took for migraines. She cleans houses, and she started taking the pills after being offered some by a client’s daughter. The addiction blossomed and then flourished, one illicit pill, then one prescription at a time. She’d obtain 80 pills a month and use them all. She was at it for about a decade.

Anderson, 63, looks through her dark-rimmed glasses in a constant squint. She’s still trying to figure out how she developed her addiction and is uncomfortable with that designation. Unlike her son’s use, hers didn’t declare itself with menacing dealers and prison time. She may have gotten a few pills without a prescription, but the rest had come with a doctor’s approval. Even when she finally confessed to her doctor that she thought she had become addicted to the pain pills, she says he just wrote her another prescription and said it was her choice whether to take them. By then, she wasn’t taking them to alleviate pain; she was taking them to ward off withdrawal. She doesn’t like talking about it with her family. But when her son told her about buprenorphine, she saw a way out.

Fischer grabs his cigarettes and phone from his truck and takes a seat in the back of his stepfather’s beige Lincoln Town Car. His mother gets in the front seat and immediately asks her son if he is warm enough. Is he too warm? Does he want a Pepsi? Does he want a blanket? She will repeat these questions on the hour.

Fischer’s stepfather, Bob Anderson, 71, stubs out a cigarette and quietly takes the wheel. The big Lincoln crunches through the snow-covered street, past the mobile homes, the church on the hill, and the tiny government buildings along the main drag. The GPS on the dashboard says 332 miles to go. They won’t see daylight until they are near the Wyoming border.

Lusk, Wyoming, as seen through the Lincoln's window. Jason Cherkis / The Huffington Post

There’s a reason why Fischer and his mother must wake up before dawn, share road space with 18-wheelers and mule deer, and waste a day off from work. Addiction medicine is still not mainstream medicine. The federal government has helped to keep it that way.

To become certified to prescribe buprenorphine, doctors have to first complete a one-day training class on addiction medicine. Then, for the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, certified doctors are limited to accepting only 30 patients with opioid addiction at any one time. They can move up to 100 patients in their second year of prescribing.

The last year has seen remarkable progress on the policy front. Lawmakers from both parties are becoming more open to less punitive approaches to the nation’s opioid epidemic, like making sure that drug courts are receptive to medication-assisted treatment. The federal government funded MAT programs and encouraged states to do the same. But for those close to the crisis, the progress still can be hard to see.

In late October, President Barack Obama announced a series of measures to address the shortage of doctors certified to treat opioid addiction with medication. He ordered all federal agencies overseeing health care to review their policies and remove any obstacles to receiving medication-assisted treatment. The president also set a target of doubling the number of certified doctors.

Obama’s actions followed a September declaration by Sylvia Mathews Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, that her agency would begin the process of reworking the patient caps to expand access. Noting that medication-assisted treatment “is a high priority” for HHS, a department spokesperson told HuffPost in late December that the agency is “working quickly to update the rules.”

Making sure that every opioid addict who wants medication-assisted treatment can receive it — the Obama administration’s goal — will require a major shift. As of December 2015, only 29,157 doctors were approved to prescribe buprenorphine. Just 18,600 are listed on the government’s publicly searchable Treatment Locator, and fewer than 10,000 can treat the legal limit of 100 patients each, according to a Huffington Post analysis of government data. Less than 4 percent of certified doctors practice in rural areas.

The real numbers could be even lower. Government databases list doctors who have retired or face licensing issues. They don’t distinguish between those who may decide to prescribe buprenorphine only for chronic pain and those who treat opioid addiction. At least 4 in 10 doctors certified to prescribe buprenorphine don’t prescribe the medication at all, according to one review of physician surveys.

The latest available data on America’s opioid epidemic underscore the need for action. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined 28 states and found that between 2010 and 2012, heroin overdose death rates had doubled. And those numbers continue to surge. More than 28,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2014, an all-time high, according to a recent CDC report.

The Obama administration is not acting fast enough, says Dr. Andrew Kolodny, the chief medical officer for Phoenix House, one of the largest addiction treatment operations in the country and one that introduced MAT into a previously abstinence-only model a few years ago. “It’s very frustrating,” he says. “They’ve got to do something.” Doctors working in the New York regional offices of Phoenix House — including Long Island, where the epidemic is most acute — are at their patient limits. “This is interfering with our ability to accept new patients for buprenorphine,” Kolodny says.

In states overwhelmed by the opioid crisis, certified doctors can’t keep up with demand. Dr. Mina Kalfas, who is based in Northern Kentucky, says that since 2013 he’s lost at least two potential patients who had fatal overdoses after he turned them away. One died two weeks ago. “I wanted to throw up,” Kalfas says. “It’s the limit. That’s the only reason.”

Beyond the emotionally draining aspects, doctors face other challenges in treating opioid addiction. They aren’t given much, if any, addiction training in medical school, so they have to learn on the job, which can be difficult. The Drug Enforcement Administration will visit doctors who go over the patient cap. State Medicaid officials may try to reject the patients or refuse to reimburse doctors over problems with paperwork. Local counseling services may be unwilling to provide therapy to their patients. Other doctors may see these physicians as on the fringes of medicine.

The rate of certified doctors looking to treat up to the maximum 100 patients has slowed. When the federal government began allowing physicians to treat more than 30 patients in 2007, nearly 2,000 doctors applied, according to data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Since then, the rate of doctors applying has fluctuated but slowed overall: 26 percent fewer doctors sought to treat more patients in 2015 than in 2007.

“I get smeared with the same stigma that my patients get smeared with,” says Dr. Mary McMasters, who practices MAT in Augusta County, Virginia. “I was at a gathering of physicians. There were 18 physicians there. Three people came up to me afterwards and asked me if I was a psychologist. Then I was asked if I was a physician’s assistant, and I was asked if I was the wife of the guy sitting across the table from me. Another asked if addiction was a real area of medicine.”

The demands of a rural community, where resources are spread thin, makes it more difficult to focus a practice on addiction medicine. Even when doctors in more populated areas want to treat more patients, they often aren’t being encouraged by local public health officials or hospital administrators. Dr. Herbert Roehrich, who practices in Kenosha, Wisconsin, says he had to limit the number of buprenorphine patients he took because he was already overworked. There’s too much need for everything else among his patients. “I couldn’t take another patient to save my life,” he says.

The government’s caps have helped to create a black market for buprenorphine. Fischer says a friendly drug dealer educated him on the medication. He was living outside San Antonio, Texas, at the time, shooting up three grams of heroin a day, and often using it in tandem with methamphetamines. One day, he recalls, his dealer asked him if he ever thought about getting sober. Fischer told him he thought about it all the time. He just didn’t know how.

The dealer handed him some Suboxone and a pamphlet for an Austin clinic. Once Fischer started going to the clinic, he began taking the medication as prescribed. “I can do this,” he remembers thinking. “I don’t want to use anymore. It was like, just, bam!”

In Wyoming, the state Fischer and his mother now have to drive through, there are only 37 doctors certified to prescribe buprenorphine. More than a third have retired, moved out of the state or don’t provide medication-assisted treatment. After Fischer left San Antonio and returned to Rapid City, he and his mother started making trips to a doctor in Gillette, Wyoming. There, they would sit in a room of what used to be a bordello. The doctor would video-conference with them for five minutes or so. The visits — and the prescriptions — stopped when the doctor abruptly ended his practice.

They had to search for a new physician. At one point, Fischer secured an appointment in Casper, Wyoming, only 250 miles from home. But the doctor turned him away when she realized he wasn’t looking for buprenorphine to treat chronic pain. Instead, Fischer says, she wrote him a prescription for Xanax.

Fischer and his mother found an online directory of prescribers. They called dozens of them. “I didn’t think I was going to find a doctor,” Fischer says. “We tried all over. We tried all of the surrounding states: Montana, Wyoming, Minnesota, Nebraska, Colorado.”

Meanwhile, Fischer conserved his medication by cutting up the tablets and taking only half his daily dose. He grew so desperate that he called a few dealers he still knew and asked if they could sell him some Suboxone. But they were charging too much. Finally, after a month and a half of looking, Anderson found the doctor in Fort Collins. It was random luck: She called on the right day at the right time. The doctor had two openings.

On their first trip, Fischer started to feel a little sick from withdrawal. He was all out of buprenorphine. His mother still had a couple of tablets left. She handed him one so he’d be OK for the ride down.

Somewhere on the road in Wyoming. Jason Cherkis / The Huffington Post

Fischer’s stepfather, Bob, traces the southern edge of the Black Hills. A gray fog sneaks up, keeping visibility low. Wyoming announces itself with pocked roads and the worry of pummeling winds. The land opens up to scrubby, snow-covered prairie and barbed-wire fence stretching for miles. Here, Fischer says, even a beautiful day can feel desolate.

At the first rest stop, their usual one, a flyer pinned to the bulletin board outside the unheated bathrooms lists suicide hotline numbers: “If you are depressed please Avoid drugs and alcohol. Talk to someone, express your feelings.”

The temperature drops from 6 degrees to 3 to 1. A road sign reads “Pass With Care.” Cell phone bars vanish one by one, until there are none.

Fischer and his mother view these monthly trips as a chance to make up for lost time. Anderson gave birth to him 15 years after her first-born son and a decade after her daughter. He was a smart, athletic boy — a member of the swim team — but he became a handful after she divorced his father. She lost custody for a while. He ended up doing time in juvie.

Heroin came before high school graduation. Fischer never made it any further, blowing through his college fund on meth and cocaine, heroin and pills. He moved to Texas to be near his sister, then to Montana, then to South Dakota and then back to Texas — always hoping a change of scenery would do him good. Instead, despair followed. He contracted hepatitis C and lost regular contact with his two older children. His mother never cut him off. But they spent years apart, a little wary, off in their own corners.

Anderson struggled with the shame of her own addiction. Her family tree was full of relatives with the disease. She didn’t drink or smoke. She’d only started taking the pain pills for migraines, but then she couldn’t go a day without them. When the pills started to wear off, she’d take another one or two. “Here I am, 50 years old, acting like the big stupid,” she says. “I’m a mom, a wife, an adult woman. I felt terrible about myself.”

When Fischer started taking buprenorphine, his mother immediately noticed a change. He used to avoid her phone calls. Now, he’d call her just wanting to talk. Early on in his recovery, he asked his mother if she wanted to go to lunch. He never used to be able to sit still long enough for real conversation. At their lunch, they talked for nearly two hours. Afterward, Anderson went home and cried. “You never think that day is ever going to come,” she says.

After Fischer moved home from Texas and found the doctor in Gillette, Wyoming, his mother and stepfather would drive him there for his buprenorphine prescription. Anderson at first didn’t pick up a prescription for herself. But watching her son, she decided to give it a try. Initially, she didn’t tell her son. Instead, she’d regularly make two trips to Gillette — one in secret.

Anderson isn’t sure why she hid her own recovery from Fischer when he was going through a similar experience. “I suppose because I was embarrassed,” she says. “When I did tell him, he was glad.” They eventually started arranging their appointments for the same day.

They now have stories about rest stops, and a favorite truck stop in Lusk, Wyoming, where they get coffee and French toast.

Returning to the Lincoln, Anderson joins her son in the backseat, squeezing her thin frame between the window and the cooler full of Pepsi cans. Fischer hugs a pillow and drifts off to sleep. We pass a 100-car coal train and cattle waiting to be fed.

The long drive, Bob says, is “a small price to pay.” He wasn’t sure what to do about his wife. “She’d just kind of fall apart, space out,” he says. “I knew she was doing way, way too many. But she’s kind of a stubborn girl, you know?”

It was the same with his stepson. “I think he finally came to that conclusion that ‘I don’t want to do this, but I don’t know how to get away from it,’” Bob says.

They hit Chugwater, Wyoming, and the next rest stop, where the wind is so fierce that Anderson decides to stay in the car. Fischer wakes up for a cigarette, huddling with his stepfather in the entrance.

“It’s scary living without your best friend, your lover, whatever you want to call it, because heroin is all of those things,” Fischer says, joining the conversation back in the Lincoln. For five years, he wanted to quit but was stuck. “Just didn’t know how, just didn’t even know how to confront it. It just seems like I been in that world for so long, to live any other way was almost …”

His mother cuts him off.

“The rehabs weren’t helping,” Anderson says.

“Right,” Fischer says. “I felt like I had done it for so long.”

“I was only ever given one option and that option was rehab,” he continues. “There wasn’t any other option. It was either jail or rehab or death. That was your way to get out. It’s kind of like getting jumped into a gang or something. It’s blood in, blood out. There’s no way to get out. The methods that were available didn’t work for me. I know that.”

“I don’t believe that rehab would have ever cleaned you completely,” Anderson says. “I don’t think it would have ever made you completely clean.”

“It would have had to have been a divine something,” Fischer says.

Dr. Clark McCoy sees patients from all over the West. Jason Cherkis / The Huffington Post

Dr. Clark McCoy runs the Front Range Clinic in Fort Collins in the basement of a nondescript building occupied mostly by dentists. After he opened in October 2014, his waiting room soon filled up with people looking to start medication-assisted treatment.

But McCoy wasn’t just treating opioid addicts from Fort Collins, a college town an hour north of Denver. He was seeing patients from all over the western United States: a manufacturing worker from Nebraska, an oil field worker from Utah, a sudden cluster of patients from Denver who had been left high and dry after their doctor closed his practice — and now, a mother and her son from South Dakota. One outpatient coordinator in Cheyenne, Wyoming, says she has referred no fewer than 50 patients to him.

There’s a simple explanation for all the business. McCoy, 46, has become an instant fixture in the region’s drug treatment system because other doctors aren’t willing to do the work. He reached out to other physicians when he opened, asking them to join his clinic. Most didn’t return his phone calls.

“When you decide to start working with Suboxone, you do open yourself up to being a little bit of an outlier within the medical community,” McCoy says. “I think I am OK with it. I feel like I’m doing the right things. I feel like I’m helping an underserved, ostracized population.”

Other doctors told him they didn’t see a need for the clinic. Even those specializing in pain management, where opioid addiction among patients is always a risk, dismissed him. “Quite honestly, they don’t like what I do,” McCoy says. “They are uncomfortable with the subject.”

McCoy recognized the unease. He’d been just like them when he started out, in 1997, with a family practice in Gainesville, Florida. He had a lot of patients who had been on opioids for decades, some of whom had migrated from other doctors to him. He knew they lied about their need for the painkillers. “I can’t emphasize enough how terrified a person is having run out of her opioids,” he says. “They are acutely aware of what withdrawal is. It becomes a very anxiety-provoking thing.”

While doing consulting work at a psychiatric ward with an addiction unit, he learned about buprenorphine and saw how patients detoxed with it — how quickly they began to feel normal. Not using it was like practicing medicine in the Middle Ages, he thought.

Like most other physicians, McCoy had not been trained to treat addiction in medical school. So he decided to educate himself, he says, and to get certified to prescribe buprenorphine. He believed that if he could offer the medication to his patients, he might be able to talk to them about quitting the painkillers. He remembers how scared he was talking to his first patient — a person with an opioid addiction just like Anderson’s. The nerves showed so badly that his patient grabbed his hand and said she was scared. He told her he was scared, too. The two cracked up at their situation.

McCoy knows that what he’s doing has to be a calling. But can it, he wonders, be a lasting one? When he reached the 100-patient limit this past March, he convinced his nephew, a certified doctor practicing in North Dakota (he was not prescribing buprenorphine at the time), to help. Now, once a month for a week, his nephew travels from North Dakota to work at the clinic. “This is not really sustainable,” McCoy said several months ago.

When the Obama administration announced plans to adjust the cap and increase access to buprenorphine in September, McCoy and his wife wept at the news.

The doctor realized his clinic had a chance. He started to accept Medicaid patients because, with more patients coming in, he could afford to take the lower reimbursement rates. But he’s gambling on the president’s plans, which haven’t gone into effect yet. “That’s the only thing that stresses him out,” his wife, Allison, says. “He has to figure out what he wants to do long-term. I think he’s getting impatient.”

In late fall, McCoy took a second job as medical director of a county jail. He’s about to start a third job running a medical detox unit at a newly opened psychiatric hospital. He plans on working at the hospital in the mornings and seeing his clinic patients in the afternoons and evenings. He needs the extra money to help support his four children and to keep the clinic going.

If McCoy’s hold on the clinic is tenuous, his patients’ access to it is even more uncertain. Some carpool from Wyoming or catch rides from Denver. This past summer, one took a two-hour cab ride from Colorado Springs. Some just stop showing up. One patient’s mother recently called from western Nebraska begging McCoy to write her daughter a prescription. Her daughter hadn’t been able to make it to the clinic in more than five weeks. She couldn’t get time off from work.

When Fischer and his mother first called for an appointment several months ago, McCoy was suspicious. Why would two people want to drive hundreds of miles to pick up Suboxone prescriptions unless they were planning to sell the pills on the black market? He soon realized that they were just like so many of his other patients — the ones living in rural counties with no way of getting the medication that could save their lives.

On this day, Fischer and Anderson are early for their appointments. McCoy doesn’t make them wait long. Fischer’s visit goes smoothly. He tells the doctor about his new job and new responsibilities, but doesn’t mention his worries over the phone call with his boss the night before. McCoy tells him he’s showing signs of real progress.

An office assistant escorts Anderson to a bathroom so she can provide a urine sample. It’s part of the clinic’s protocol to check for any signs of relapse. Anderson is then shown to a bare exam room, where she anxiously takes a seat on a small gray couch near a window. McCoy soon enters and swivels his chair over to her. In a soothing, reference-desk voice, he asks how she’s coming along with the pills.

“I would say better,” Anderson answers, her voice softening to match the doctor’s. “I would say pretty darn good.”

McCoy wants to know when she is taking the medication. The meds need to become part of her routine — not something she takes only when she thinks she needs it. This notion isn’t easy for someone who spent years taking pills to ward off withdrawal symptoms.

McCoy is encouraged by Anderson’s response: It seems like the schedule is becoming automatic. He gets her urine test back and reads over the results. There are no signs for concern. The goal, he says, is for her now to return to therapy, something she’s had to skip because of her housecleaning job and caring for Fischer’s new baby. Her previous sessions, she tells McCoy, were dominated by concerns about her son.

McCoy wants her to be more consistent with therapy because eventually he would like to taper her off the buprenorphine. He wants to lower her dose, he says, only when she feels ready.

The mention of tapering startles Anderson. “I don’t know if I’m ready for that yet,” she says.

“And I’m not sure you are either,” McCoy says. “But I’m bringing it up to get you thinking about it.” He knows she may not be able to make the 332-mile commute to see him indefinitely.

“Now my blood pressure’s really up,” Anderson says. “I can feel my heart.”

“It’s always a discussion between us,” McCoy assures her. “Physically your body has to be ready to do it. You’re getting there. You’re not there yet, but you’re getting there.”

Comments