If you’re a woman, you may have at one point thought to yourself, “My partner couldn’t find my clitoris if I drew a map.” But did you ever stop to wonder if you could draw the map in the first place? Or if the map you’d draw would be accurate at all?

What if, when it comes to the sexual anatomy of women, we’ve been looking at a completely inaccurate representation?

In order to understand the significance of that, you have to zoom out. Outside of yourself. Beyond your town. Past the borders of your country and continent.

Now close your eyes and imagine the whole world. What do you see?

Chances are high that one of the first things that comes to mind is not Earth itself, but a map of it. One map in particular:

Credit: Getty Images

Known as the Mercator projection, after the cartographer Gerardus Mercator, who first conceived of it in 1569, it’s ubiquitous in classrooms around the world.

The map demands authority. You can read latitude and longitude lines and see precisely how many miles have been squeezed into an inch. Surely there’s an exactness to where the blue of each ocean meets the greens and browns of each continent, to the way the textured lines that indicate a mountain range’s rise and fall.

But at some point, perhaps you stumbled upon the knowledge that Greenland is not the same size as the continent of Africa. Eventually, you may have learned that the Mercator projection has a big problem.

While all maps distort scale, the Mercator projection does so in a way that makes elements appear larger the farther away they are from the equator.

Astronauts have taken pictures of the Earth through the spaceship equivalent of a rearview window. Satellites regularly photograph our planet from the sky. We have pretty significant evidence that Mercator got the scale all wrong.

Yet his projection remains the authority all the same. Today, when children learn geography in school, they might not see Mercator’s poorly proportioned countries and continents on a wall-mounted map. But they will likely see it through the glare of a screen: even Google Maps uses the Mercator projection.

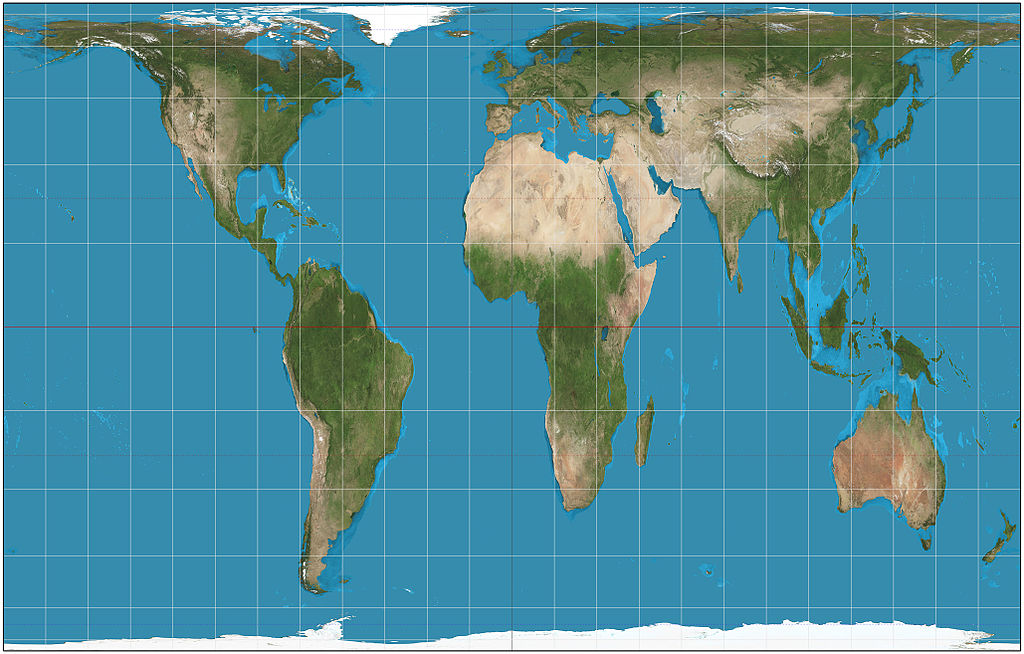

Others have created alternative projections over the years that tried to do better justice to the Earth’s geographical scale. In recent years, many have advocated for the Gall-Peters projection, which depicts the size of each continent more accurately — but creates more unfamiliar shapes:

Credit: Strebe / Wikimedia Commons

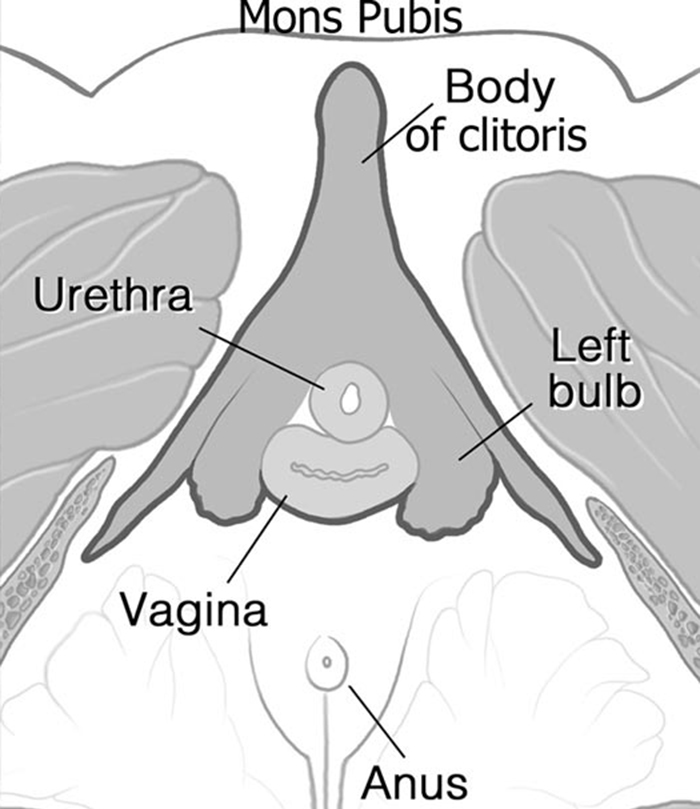

Human anatomy is nothing but a map of the body’s geography. And up until 1998, when it came to the anatomy of the clitoris, the world at large was putting its trust in an inaccurate map.

Those in the medical community had no reason to assume they were wrong. The anatomical “maps” that anchored their education must have seemed as sturdy and steadfast as Mercator’s, with every organ plotted and every muscle annotated.

There was little reason to question anything, especially the anatomy of an organ as seemingly tiny and inconsequential as the clitoris.

But in the early 1990s, that’s exactly what one enterprising young doctor did. Helen O’Connell, an Australian urologist, took note of the many machines and mechanisms hooked up to men during medical procedures like prostate surgery — devices meant to keep surgeons as far away from nerve endings in the male sexual anatomy as possible.

She wondered why there was no equivalent to help protect the female sexual anatomy during surgery. Without these precautions, how could doctors know they weren’t cutting into clitoral nerves during routine procedures like hysterectomies?

She suspected her reference books wouldn’t offer much help. “As a surgical trainee, you have to study these anatomy texts over and over and over, so I knew that everything was detailed when it came to men and very little was when it came to women,” O’Connell told The Huffington Post.

So she set out to find the missing details herself. In 1998, she published her findings. She revealed to the world that the clitoris had an internal and external structure, demonstrating that in its entirety...

It didn’t look like this:

Credit: Yestadae / Wikimedia Commons

Instead, it looked like this:

Credit: Dr. Helen O'Connell

In other words, Helen O’Connell had pulled back the hood.

O’Connell would continue her research. In 2005, she published another study, asserting that the clitoris extends behind the vaginal wall. “If you lift the skin off the vagina on the side walls, you get the bulbs of the clitoris,” she wrote.

While O’Connell’s findings were groundbreaking, they have yet to infiltrate popular culture and sex education in a meaningful way. The anatomical map has not been altered to account for new discoveries.

It is easy to dismiss inaccuracies in anatomical or geographical mapping. But maps are more than guides used to navigate a landscape. We rely on them to help us conceptualize and better understand the things we cannot see. And we trust their authority.

When it comes to the way we think about female anatomy and female pleasure, we’re suffering from an underlying problem. We’re still using an old and outdated map — one that’s in desperate need of an update.